“Sue Coe paints horror beautifully, ugliness elegantly, and monstrosity with precise sanity,” wrote Glenn O’Brien—RIP—in 1984 for the debut review of Sue Coe’s work in Artforum. The claim rings true today. Her anti-career career as someone “double-parked on the highway of life,” as she puts it, has been one of nonstop art as activism. “Graphic Resistance,” a survey of fifty works from the past forty years, is on view at MoMA PS1 in New York until September 9.

I MAKE ART FOR PEOPLE ON THE FRONT LINES. That’s my family: a community of activists who are not artists but who want to use art as a weapon. That’s who tells me if something is working and how I can make my art more effective. Some of my work is direct propaganda; some of it is visual journalism. I was an editorial artist for many decades—that’s what I’m supposed to be. At sixteen, I began doing work for newspapers and never looked back. But at some point that changed into doing my own research and books, as opposed to illustrating somebody else’s words.

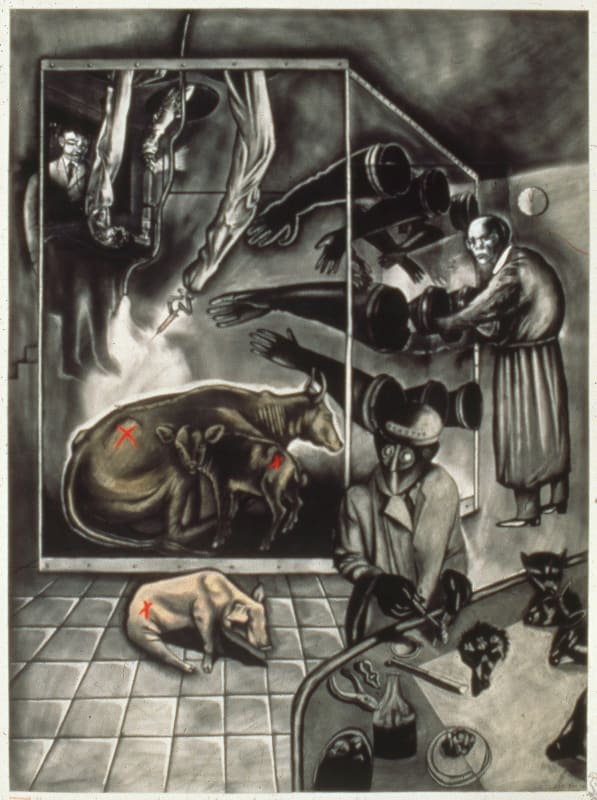

Usually an artist is known for only one body of work, but I’m lucky that I’m known for two: the ongoing project about animal rights and the rape painting, which is now at MoMA PS1. The former work continues, and I’m always learning. As I see it, animals liberate themselves. They need our help, but it’s not Lord and Lady Bountiful saving them. I’m aghast at how animal rights today have become all about the human diet—about being gluten-free. Animal liberation is a social-justice issue, and I’ve always promoted the abolitionist approach: eradication of all use. But now animal rights have been twisted into the market, where the meat industry disrupts itself by buying up vegan food producers.

Art always has to go beyond human health, human drama, and human issues. It has to be about social justice for all animals, including us. I initially made that connection as a kid in England after World War II, growing up around bombed-out ruins and living next door to a slaughterhouse. As a child, I was forced to see the correlation between war, violence, and fascism, and animal cruelty and abuse. Once I figured that connection out, so early on, I realized that the Other is always at risk.

When I was a vegan back in the late 1970s, there were like ten of us. Now it’s like half the student body at places where I teach. Food animals are raped every time they are inseminated and are molested almost constantly. It’s only within this animal rights movement that you can have “rape-free Mondays” and “child molestation–free Tuesdays.” Would saying “I feel like raping a child right now” be acceptable in any other social-justice movement? No. The mistake of taking “baby steps” toward progress has happened in nearly every social-justice movement, and animal liberation is no different. Yet, there can’t be any baby steps in this movement because there are no baby steps for an animal going into a slaughterhouse. They are babies, and they’re being slaughtered.

For me, there’s no difference between someone who works in the slaughterhouse and someone buying animal products from Whole Foods. They are morally exactly the same. Except one is usually poorer—the professional life span of a meatpacker is six months. Oh, and meatpacking places are called “harvesting centers” now. It’s beyond Orwellian how the language changes.

What should be a rights movement has become a welfare movement. We need to understand how welfarism is keeping the system going. Welfare is always said to be a panacea that supposedly will make things better in the long term, but it doesn’t. That’s why my message carries an element of hopelessness. But there’s something else: a dignity in struggle. There’s a dignity in having comradeship. There’s a dignity in not having our brains so destroyed that we think any problem has to be solved by a market solution. Unlike in the 1980s, people don’t believe the market is going to provide the solution anymore. So that’s changed.

As for feminism, the first review I ever had in the New York Times said I was a feminist artist. It’s always been difficult for me to be in two bodies. People ask, “How does it feel to be a woman artist?” I mean, how does it feel to not be? But the more serious answer to the question about feminist content in my work is that I’ve always seen that as a bourgeois movement controlled by the dominant classes in America. If Hillary Clinton breaks a glass ceiling, does that really change anything?

I’m much more focused on what I’m working on now: Dump Trump. I could just do it in my sleep.

— As told to Lauren O’Neill-Butler