In "President Raygun Takes a Hot Bath" the former president does just that, in front of a framed dollar sign, and smiles with pleasure as a monster labeled CIA cuts off the heads of its victims. "The real war is between the world's people and the arms manufacturers," reads the accompanying text. "It is absurd for them to put us in uniform and require that we kill each other for their profit gains."

In a work protesting then-British Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher's "refusal to apply sanctions against the South African regime," Coe created "Bothatcher," depicting Thatcher and South African President P. W. Botha as a two-headed spider branded with a swastika.

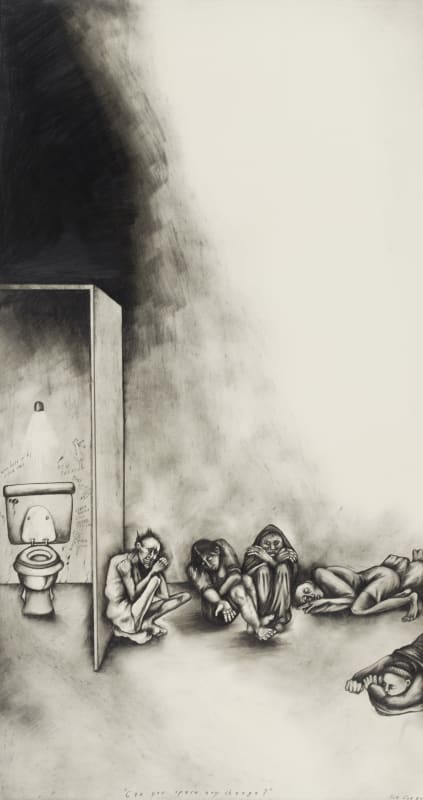

In a work on the homeless, she depicted a group of emaciated women huddled on the floor of a bathroom in "Women Living in the Toilet at Penn Station."

She has dealt with the Ku Klux Klan, landlords, the stock market, police brutality and more abstract subjects such as greed. One of her mottoes is "Heroes: Those who exploit best. Losers: Those who identify with the rest."

British by birth but a resident of New York for the last 20 years, she does not hesitate to take on either her native or her adopted country, in works that are not easy to take. They are unremittingly gloomy and filled with people depicted either as butchers and monsters or their victims.

But, she said in a recent telephone interview from New York, she sees her art as actually hopeful.

"I think it's extremely optimistic. Doing this kind of work is similar to a psychological process, when your doctor in analysis says you have to feel bad to get better," she says.

"You have to have a recognition that things are real and they're very bad. It's a strange process, but it does work. Denial of reality doesn't in the long term make you feel good, and seeing art work that's supposed to be entertaining -- that's not the role of art, and it hasn't been historically."

At 42, Coe has come to the fore among today's socially conscious artists. The critic Donald Kuspit has called her "the greatest living practitioner [of] a confrontational, revolutionary art."

But she didn't start out that way. Brought up in a working-class area of London, she studied graphic design at the Royal College of Art because, a recent essay on her states, "[it was] the only branch of the fine arts that promised a steady income."

Turning from failure

In 1972 she came to the United States seeking work, and, she says, it was failure that led to her success. "I started off on the recipe page of the New York Times, making food look good, and when I couldn't do well enough making the roast duck look good, I thought I might as well do what I wanted to do."

Influenced by such artists as Goya, Daumier, Otto Dix and Jose Clemente Orozco, Coe began making socially conscious art as long ago as 1974. Interested in getting her message to as widean audience as possible, she has worked in the print medium, has had her work published in newspapers and magazines, and has made series that have become books.

They include "How to Commit Suicide in South Africa" (1983), "X (The Life and Times of Malcolm X)" (1986) and "Police State" (1987). The last also became an exhibit that traveled to 11 museums in this country and Britain.

For the past seven years she has been working, among other things, on "Porkopolis," an indictment of the meat industry that has been made into an exhibit seen in five cities.

Her work, she says, is an effort to bring people together to make change. "I think it's like when you go up to a Coca-Cola machine and put in 75 cents and nothing happens so you kick it and shake it. It's very important to have a witness to say to, 'Look, it took my money and doesn't give out anything.'

"My work is about having a witness. Things don't change when one person sees something. It only changes when you tell somebody; then it becomes a group vision. When I do these drawings, it's like, 'Look through my eyes, so you can see it, too,' and someone sees it and says 'Yes, that happens.' "

Often described as an opponent of capitalism, she sees capitalism as its own worst enemy. "There are only two economic systems known to human beings; one is socialism and one is capitalism. Capitalism will destroy itself -- its contradictions will destroy it. Whether it will take all human beings off the face of the earth with it -- that's the question."

Among those who know Coe's work well are Baltimore collectors Jim and Susie Hill, who have been acquiring her work for some years and own both books and prints. Although he's obviously an admirer, Jim Hill has wondered aloud whether Coe sees anything at all in the world to celebrate.

Reason for celebration

She doesn't hesitate to take that one on. "The fact that I do this work is the celebration, because to get this work published -- I don't know if you can truly comprehend how difficult this is. Magazines and newspapers don't want to see art work about slaughterhouses and radiation. To get something published is very difficult, and not just for me individually. When I see something in print that's about reality, I feel good."

And despite the fact that she depicts human beings doing horrible things to one another, she maintains that most people are not only good, but too good for their own good: "People work in soup kitchens and work to ameliorate the conditions of others all the time, but it's not particularly newsworthy. In Bosnia it's never stressed how people are working together. That's not the emphasis.

"How come we've survived this long? Because we cooperate. If we didn't cooperate with each other, the human race would have been dead centuries ago. In fact, and this is a peculiar thing, we're too good. That's how come we're exploited by a tiny minority of corporations who do what they want. We allow it to happen. We cooperate. That's our nature -- it's not warlike."