My college degree is in printmaking, specifically woodcuts and aquatints. I’m pleased to say I attained moderate success; however, that doesn’t always translate into dollars. For me, the success barometer meant being included in the permanent collection of museums in and out of the United States.

Money has ever been a big motivator for me, but when you are a single dad in need of health insurance and a stable income, choices have to be made.

That was 27 years ago. Then, I got into the newspaper business.

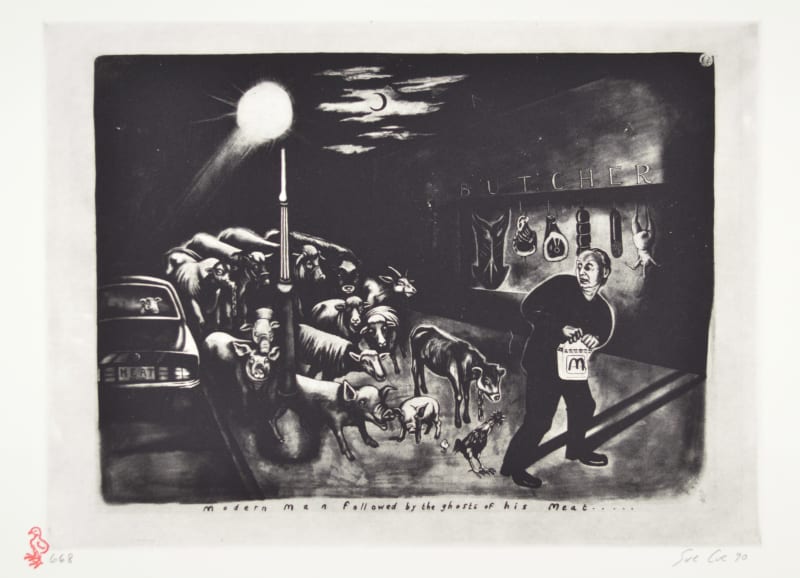

Sue Coe is a printmaker who has persevered to make a living with her art. What I find particularly intriguing is how and what she is doing.

Currently, Coe, 60, has a 30-year retrospective of her prints being shown at the Williams-Insalaco Gallery at Finger Lakes Community College. Last week, she was in the area to present a talk about her work.

She considers herself a “graphic witness,” a journalist using printed images rather than words.

Coe studied at the Royal College of Art in London and lived in New York City from 1972 to 2001. She now resides in Deposit, a village near Binghamton.

Her work is highly political, often directed against capitalism and cruelty to animals. The subject matter always involves political and social injustice. She often focuses on what she feels are the problems within the poultry, beef and pork industries in this country and abroad. She grew up close to a slaughterhouse and developed a passion to stop cruelty to animals. It may explain why Coe is a vegan.

She also has tackled nuclear missiles, Belfast, El Salvador, apartheid, big oil companies, healthcare, Aids, the federal government, President George W. Bush, child sex trade, Abu Ghraib and sweat shops — and many other controversial subjects.

Her prints are reasonably priced, and the proceeds often go to progressive causes.

The image accompanying the pictured piece cost $20. Its proceeds went to an organization fighting the poultry industry’s treatment of birds. It is an etching. I bought it to include her work in my own personal art collection. Truthfully, though, the subject matter is not one I care deeply about. I am happily a red-meat eater, even if my arteries protest.

I do, however, admire the concept of art and activism together.

Using art as a form of activism is certainly nothing new. Before Coe came the likes of Honore Daumier (1808-1897), Paul Cadmus (1904-1999), Leonard Baskin (1922-2000), Diego Rivera (1886-1957) and many, many more.

At FLCC, Coe spoke on the importance of her work being affordable. It allows many to be drawn to the allure of art collecting and get involved with social causes. Selling her art, she hopes, will help ignite social change. The way Coe sees it, art can only exist if someone sees it.

Technically, Coe is more of a draftsperson. She prefers to create through drawings, then have a printmaker reproduce multiples of the image for sale to the public. She does cut her own woodcuts, but has a printer make the editions for her.

For Coe, the content inevitably creates the form. She also feels that while truth is beauty, beauty is not necessarily truth.

Not a single day goes by where she says she doesn’t draw. It may mean sitting by a corner and watching life pass by. It may mean visiting night court with her drawing tools. She has been known to take cabs around cities at night to observe anonymously and sketch.

For anyone looking for a visual, thought-provoking experience, check out her show at the college. It runs there through March 9.